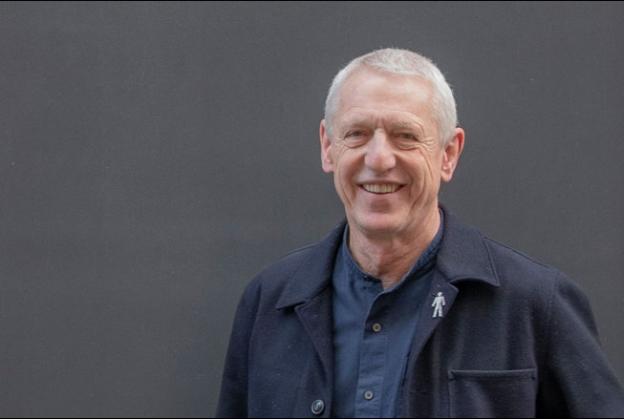

Louis Becker - Partner & Design Principal, Henning Larsen

This month, we’re delighted to introduce Louis Becker, Partner & Design Principal of leading Danish practice, Henning Larsen - founded in 1959 by an architect of the same name.

Based in Copenhagen, the firm also has offices in New York, Munich, Hong Kong, Oslo, Berlin, Sydney, Singapore and the Faroe Islands. A member of TenderStream since 2010, it describes its expertise as lying in ‘identity-creating cultural buildings, educational institutions, headquarters, and urban planning’. And in this interview, we explore some fine examples.

From Louis’ description of a number of intriguing hallmark projects, it is evident that nature and humanity and the connection between them are at the core of Henning Larsen’s work. Having joined the practice back in 1989, Louis is now in charge of breaking into the US architectural market. He tells us how that’s going, and also shares his personal thoughts on the importance of architects and architecture as we face global challenges such as climate change. But first, to Paris...

As a practice, you seem to have been on quite a winning streak, with two high-profile projects in Paris now under your belt. Let’s take the first – NØRR, a new 55,000 sqm commercial and cultural district in the northern suburb of Saint-Denis. How have you created environments that satisfy the very different demands of the two sectors the development is aimed at, and still make them work side by side?

Shaping the considerable size of NØRR was key to fulfilling its commercial and cultural functions. For a building of that size, we had to break down its volumes. If it appears monolithic, it will seem less accessible to the public. We took inspiration from the archetypal small French village, breaking architecture down to a more inviting, intimate scale. By creating smaller paths and inner courtyards, we’ve made the space more accessible, and established natural spots for outdoor cafés, recreational space, gardens, and cultural institutions. This feeds the village archetype, merging a sense of varied cultural life with the commercial activity within.

We see this inside, too: the building’s offset volumes diminish the presence of long windowless halls, instead favouring common social hubs linked by shorter and wider corridors. These feel more intimate, and become more social. Overall, we felt that this sort of accessible compartmentalisation was key to balancing the commercial and cultural aspects – It softens the boundary between urban and professional life, and makes it easier for the two to co-exist and interact.

You’ve also been selected as part of the team for the transformation and expansion of the Paris Opéra Bastille. Can you tell us a little about what the plans are for this world-famous performance space?

For us, this is an opportunity to bring new life to this Paris landmark. We want to open the Opéra up to the surrounding activity in the district, and to do so in a way that merges our own architectural identity with the legacy of the original architect, Carlos Ott.

The redesign establishes a dual-level ‘indoor street’ in the Opéra’s foyer, giving a space where Opéra patrons and the general public can interact. Toward this goal, we’re also connecting the building with the adjacent Viaduc des Arts, which links it to the Viaduc’s own activity, while exploring the threshold between the natural and urban environments.

Of course, we want to improve things behind the scenes as well. We’re going to expand performance and rehearsal spaces, and shape backstage spaces to give greater technical function to the scene workshops, stagehand functions, and everything else required to boost productivity and quality of life for the Opéra Bastille’s set and costume crews. Overall, we’re trying to make a better performance experience on both sides of the stage.

Henning Larsen also has an impressive track record in workspace design. We’d like to ask you about four such projects, starting with the Nordea HQ in Copenhagen. How has the concept of transparency between employees, clients and the surrounding city been reflected in the design?

We felt that emphasising transparency in this project was a way to build a more trusting, inviting relationship between the financial sector and the greater public.

For this new workplace, transparency needed to be inside and out – The building users needed to experience the same ideas that the building radiated outward.

Inside, it feels like the entire bank has transformed in to a small city. Employees work in large, naturally lit atriums, and have great opportunity to work in collaborative close contact throughout the day. At the same time, we’ve designed the building to open toward the public. Through transparent street-level windows, passers-by can glance directly into conference rooms and offices, able to observe the daily inner workings of one of the largest banks in the country. The building’s two central atriums are connected with a publically-accessible inner thoroughfare, where pedestrians can pass through and look inside. We felt this gesture was an important statement of trust between Nordea and the public.

At the same time, the transparent façades offer great views outward to the greenery of the Amager Faelled park, making that transparency a two-way street. Overall, the building puts colleagues in touch with one another, puts the financial institution in touch with the public, and through a connection to nature, grounds Nordea in its Danish roots. We feel it’s a great step for transparency in the financial sector.

Due to extensive mining, the Swedish city of Kiruna has had to relocate its entire city centre three kilometres east. The new city hall and community centre, “The Crystal”, is the first building in new Kiruna. How has its architecture symbolised the sense of a new beginning?

Relocating a town is more than just logistics. It’s an emotional process, as residents lose the sense of place that is critical to their individual and collective identity. Our hope was to make this new town hall not only an effective seat for the local government, but a space that celebrates Kiruna’s history and establishes an enduring symbol of local identity. The new beginning is physical and symbolic… The Crystal reuses the bell tower and the door handles from the main entrance of the original town hall, giving a sense of new life to existing history.

At the same time, we wanted to emphasise the new town hall’s social function, acknowledging the need for a gathering point during this new chapter. The city hall is a circle where the outer building volume contains office space for the departments of Kiruna Municipality, but the core of the building is a dedicated social and cultural space.

We included public exhibition halls, a café, workshops and a museum, to establish a foundational common realm for the new city centre. We wanted to make a living room for Kiruna, a place to gather in a time where a new house might not yet feel like home. The Crystal creates a space for long-time friends and neighbours to gather, preserving this sense of social unity during the transitory period of Kiruna’s relocation.

And how has the natural world been used at the Biotope in France to bring heightened wellness into the workspace?

In terms of local context, the site of the Biotope is part of a ring of parks, forests and gardens surrounding the city centre, so we saw the opportunity to bring this green appeal into the built environment. We’ve flooded inner atriums and interior workspaces with natural daylight, and incorporated open-air balconies that give easy access to courtyard gardens and the surrounding parks.

The building’s terraced green roof is perhaps the Biotope’s most distinctive feature, and we imagine it to become its new social commons – for co-workers to meet in the gardens, rather than in a conference room. It’s been shown that access to green space in the workplace makes people happier, and helps them stay focused throughout the day. We want to put that at the forefront of the Biotope, to ensure that nature is never out of reach.

It’s been said that you tackle every project based on the conviction that architecture ‘must speak directly to users and give back to the society in which it exists’. Can you explain to us how this approach is especially evident in Siemens’ new global headquarters in Munich?

The Siemens global headquarters is in a great position in Munich – It’s situated right between the city’s historic centre and its museum quarter, so it’s a pivotal spot for pedestrian traffic from both locals and tourists. We felt we could make Siemens a part of this dialogue. The ground floor is public, and creates a new shortcut between these two areas of the city, guiding pedestrians through green courtyards and atrium spaces.

We feel this makes the building a sort of conduit of activity; it positions Siemens as a more active participant in urban life and fabric, not just a closed corporate space, while employees within get renewed energy from this sense of connectivity with active urban life. Like Nordea, it’s an exercise in transparency and public engagement, creating outward public value for the benefit of both building users and the general public.

We understand you’re spearheading Henning Larsen’s entry and positioning in the North American market. What are your ambitions there, and how are things going so far?

We believe our Scandinavian approach to architecture has a future in North America. The North American market presents new climates, cultures and context for us to explore, all of which require their own tailored solutions. We want to deliver better workplaces and new social centres, to build foundations for closer communities and cultural exchange, to find new opportunities for knowledge-based design.

Right now, we’re looking forward to opening the Carl H. Lindner College of Business at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio. We’ve put a great deal of work into analysing occupancy patterns and behaviour, and we’re hoping to create a social, inclusive space that helps students and faculty connect both in and outside of the classroom. We’re also finalising the planning for an expansion of the municipal government offices in Minneapolis, Minnesota, which we’re very proud of.

Among your many distinguished personal achievements in architecture, which include being awarded the coveted Eckersberg Medal from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, you are also much sought after as a public speaker. Have you got any interesting lectures or talks coming up?

I’m looking forward to connecting with young North American audiences during an upcoming speaking tour of American universities. Henning Larsen is also celebrating the studio’s 60th anniversary this year, which we’ll be commemorating in part with a series of design-focused charrettes across our global offices. We feel it’s important to put a greater emphasis on the ideas that shape how we design our world, but moreover, to create a platform to amplify new perspectives and ideas in architecture. We have a responsibility to consider future challenges in our changing world, and we see these charrettes as a means of welcoming new voices in that conversation. I’ll be taking part in these discussions, as we hope to broaden and diversify our discussions of architecture and design.

And what things inspire you most in life?

Change. All of us, and everything around us, is changing – Constantly adapting, growing, responding to the events and conditions that surround us. I think we can find inspiration in this, in the idea that there is always the opportunity to explore something new. It’s both professional and personal. For Henning Larsen, this helps us explore new methods of research, new ways to connect with and reflect the communities for whom we build, to reflect on and improve our approach to beautiful, enduring, functional architecture. At the same time, it’s a very personal concept, and one that I feel forms the core of personal growth.

If you had one wish for the future, either on a professional or personal level, what would it be?

I’d like to see architecture draw on new knowledge to solve the problems we’ll face in the future. Now more than ever, we’re seeing a global focus on climate change and sustainability efforts, and I think architects can be an even greater part of that conversation. We need to work across fields of knowledge, sourcing perspectives that haven’t traditionally been a part of the design process. This is certainly a challenge, but it also provides a critical learning opportunity: to learn more about our strengths and weaknesses, directions for development, and new ways we can use design to solve present and future problems.

I suppose this is a personal wish for professional growth – I want to see architects take the initiative in exploring how new voices, untapped perspectives and academic research can help us effectively plan for future changes and challenges.

And finally, how do you like to unwind?

Oddly enough, I love to travel, even though I do it all the time for work. It’s always a pleasure to find my way through unfamiliar cities, to make new connections and learn about a new culture. It feels like a very personal adventure every time, and as far as my work is concerned, I believe it broadens the cultural and personal understanding that informs the way I approach projects.

When I’m home I like to sail, whenever I have the time. It feels like a very intimate way to explore the world – in constant connection to the movement of the waves, always subject to the sea and the wind. It makes you pay attention to nature in a way you can’t quite find in the city. Also, it forces you to exist in the moment. It’s very tranquil in that way, very grounding. This summer, I’m looking forward to taking my wooden sailboat out to sea along the coasts of Denmark and Sweden with my family

Interview: Gail Taylor