Heinz Richardson – Director, Jestico + Whiles

This month, we speak with blues playing, bee-keeping, cycling architect, Heinz Richardson. Heinz is Director at Jestico + Whiles, a 100-strong employee-owned international architecture and interior design practice based in London and Prague, and established 40 years ago. The practice has particular expertise in major urban generation schemes, conservation and low-energy design across a wide range of sectors including housing, hotels, education, offices, retail, research, transport, and cultural facilities.

In this interview, we focus on some of Jestico + Whiles’ most outstanding housing developments, and Heinz gives us a fascinating insight into how the current Covid-19 pandemic is likely to impact on residential design in future. We also take a walk down memory lane into Heinz’s student past and a battle against unsympathetic redevelopment of a vibrant and much-loved part of London where the studio itself once stood.

Starting with the topic that’s on everyone’s lips, how do you think COVID-19 might impact on residential design moving forward? More live/work set-ups? A greater desire foroutside space?

The Covid-19 pandemic is already having an impact on the residential market. This is evidenced by reports that estate agents are seeing a surge in homebuyers seeking to move to more rural settings as working from home becomes a distinct option, and matches a wish to seek improvements in quality of life. This translates easily into a desire for more space and greater access to outdoor space.

For architects and providers of housing this will have a profound impact on the design of housing. Apartment living in urban settings will undoubtedly need to address this. Greater space standards to allow home working, generous and accessible outdoor space and homes that afford a dual or triple aspect that will greatly assist in facilitating cross ventilation to prevent overheating in summer are just some of the changes that will impact on design. Health and wellbeing will feature highly in new developments - perhaps with options to grow food and work close by in co-working space - and there will be more mixed communities to address an increasing number of social imperatives.

Perhaps also worth mentioning is open plan living and how we may start seeing a move away from this as privacy and acoustic issues become more of a concern with increased homeworking? And the likely potential for the rise of co-working in suburban, and possibly even rural, areas as city-centre living starts to become less critical for many people with home working on the rise?

You once said that ‘architectural practice has no choice but to adapt or it will surely be a species that does not survive’. In your view, what is driving this need for change?

Charles Darwin posited that ‘it is not the strongest of species that survive nor the most intelligent but the ones most responsive to change’. Architectural practice has an obligation to address the issues of the society in which it finds itself. These are wide ranging and diverse. Traditional forms of practice providing a professional service to clients are slowly evolving to become more collaborative with other more diverse agencies and to use the skills of architects to tackle serious issues such as climate change, diversity in the profession, social inequality, and the nature of our cities and environment.

Architects are well placed to be agents of change too, through becoming developers in their own right as a number have already become. The creative and lateral thinking that architects have will also see them able to suggest opportunities and ways of re-imagining our cities. Covid-19 will have a profound effect on the way we live our lives for years to come.

As a practice, Jestico + Whiles strives to ‘put humanity at the heart’ of all it does. How does that manifest?

Every action elicits a reaction of some sort and the intent behind the action defines almost universally the reaction. Recent changes to the way we need to live have caused us to reflect upon how we regard our society and especially those whom we may have taken for granted in the past.

Our practice has always considered those who work there, and those for whom we provide a service - whether our clients or those who experience the output of our studio. Leading by example is a way we strive to put humanity at our heart. We take nothing for granted but try and question the values we place upon our work. Our transition to employee ownership allows everyone to have a voice. Our work places the human condition and spirit at its heart to ensure that the result is always driven primarily by considering those who experience it.

Your employees all own a stake in the practice. What inspired this business model, and what have been the benefits?

Jestico + Whiles is one of thefirst architectural practices to havepioneered the transition from a shareholding practice to an employee owned model, almost 20 years ago. The inspiration behind this was to deal with issues of succession in leadership and to recognise the importance of the part played by all members of the practice inits success. The outdated model of the transfer of ownership to successive generations through the sale of shares wasunsustainable for contemporary practice. Future leaders could be identified according to the values held by the practice rather than financial imperatives.

This has been transformational. Everyone in the practice shares the success - both financially through a profit share scheme that rewards effort, commitment and talent - and by having a voice in the way the practice is run and evolves. We have found that we have been able to attract talented staff to join the practice through our reputation as an employer, as well as through the quality of our work. Workplace culture and attitude are increasingly becoming one of the primary concerns that is considered by people when looking for a practice to advance their careers. Jestico + Whiles hasbeen leading the way in this regard for many, many years now.

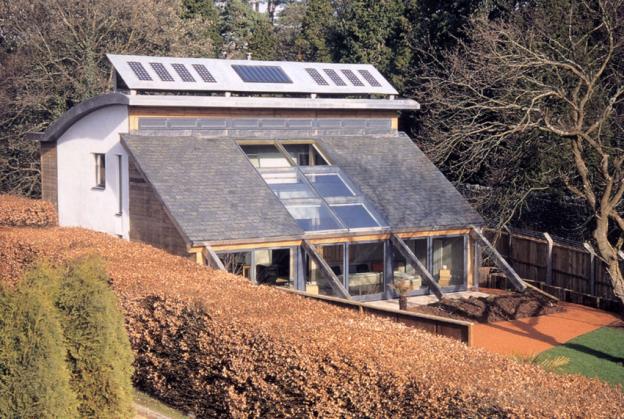

One of your personal specialisations is sustainable, low-energy design. One excellent example is the House for the Future at the Museum of Welsh Life. Can you briefly outline a few of its most distinctive features?

The House for the Future project was one of those rare projects that allows for experimentation and innovation; and to address key issues through design. It was a great project to be involved with and the key to our proposal lay in the name of the project – a House for the Future, and not a futuristic house. Given that we designed this project over 20 years ago now, the approach to the design focussed primarily on a response to climate change.

As this was the fundamental starting point, the features that informed the designare all still entirely relevant for today’s challenges.These include passive solar design, thermal mass, spatial flexibility, home working, active solar energy generation, ground source heat generation and the use of local and recycled materials to reduce embodied carbon in construction and in-use.

It was intended to be a model for housebuilding, but was so far ahead of its time that the response from the housebuilding market was that house purchasers weren’t ready for such a departure from the previously tried and tested. Regrettably,even 20 years later we have not yet begun to embrace the principles enshrined in the House for the Future on anything like the scale needed. Perhaps the impact of rapid climate change may accelerate the change in perception so desperately needed.

And you designed and built your own home – House 19 – in your hometown of Old Amersham. It’s a very contemporary house in a very historic environment. How did you marry the two? And what’s your favourite thing about living in your house?

Having spent most of my career in architecture promoting sustainability and designing buildings that address associated challenges, I have direct experience of what does and doesn’t work when designing and building sustainable architecture.

When I designed my own house in 2012, I wanted it to absolutely embrace all the issues I felt important, as well as positively responding to its place. Because it is a carbon neutral house it is a house like no other in the area, but it uses materials and forms that are commonly found within the Chilterns,which immediately creates a sense of familiarity and roots it in the vernacular of its place.

It was initially rejected by the planning committee- despite local support – but subsequently succeeded at appeal and is now used by the Local Authority as an exemplar of its kind. A prime case of changing perceptions.My favourite thing about living in the house is the ever-changing beautiful natural light and air quality internally, but above all that it performs as expected.

Continuing with the residential theme, Jestico + Whiles’ Greenwich Millennium Village project in London was based around original designs by the late Ralph Erskine. How have you worked with the original masterplan to introduce your current designs?

Ralph Erskine was a hugely influential architect whose values were expressed through his social and environmental commitment. His ideas for a millennium community at the southern end of the Greenwich Peninsula formed an approach that put sustainability and humanity at its heart - values that very much align with our own practice.

It was a privilege to build upon and expand on his pioneeringideas. The challenge lay in how to respond to the very distinctive architecture of Erskine, evolving the design language, but making it distinctly ours. We introduced the ideas of streets, mews,and terraces of houses, as well as bold apartment buildings.Equal emphasis was placed upon the space in-between buildings and the public realm as upon the buildings themselves.

The use of colour and materiality that Erskine made very much his own was something that required a bold response. We addressed it head on and developed a palette that allowed for individual characterbut created a cohesive whole.We look forward to the completion of the project in a few years’ time to experience the full effect of this completed new sustainable living quarter.

You’ve submitted planning for The White Post Lane Building as part of the vibrant Queen’s Yard mixed-use development in London, which offers flexible working space, bars, restaurants and even its own popular theatre. Can you tell us a little about the design, and how it sits within the context of the wider development?

Hackney Wick,where Queen’s Yard is located, is in the hinterland of the Olympic Park and a unique part of London that is now regenerating. A former industrial area served by the canal network,it is now home to artists,start-up creative businesses and pockets of culture.

A masterplan for the area sets the parameters for new development but our approach to evolving a response to Queen’s Yard was to respond to the history and grain of the area, and the varied roofscape of pre-existing warehouses.The material palette and design aesthetic draw heavily from the site’s post-industrial character. The homes and flexible work and retail space we have designed are extremely sustainable, with all homes having at least dual aspect, capturing distant and close views.

We have also carefully considered the public and private realm, and the relationship to the working yard and the wider public realm. One of the overriding aims of our approach wasto retain and enhance the ‘spirit’ of this part of east London and create a vibrant place of distinction, respectful of its past.

Your Pavilions, Caledonian Road development, which skirts London’s Kings Cross regeneration zone, has two challenges in particular to address: it lies within a nature conservation area, and it’s also on a railway site. How have you navigated this?

We have a longstanding client who always approaches us to sort out their trickysites. This was one of the trickiest – a site that had been used to construct the high-speed rail link (HS1)intoLondon St Pancras over the tunnel portal, a site of interestfor nature conservation (SINC) and an adjacent railway line.We had to design a humane place for people to live, around these not inconsiderable site constraints.

Our design solution was to enhance the nature value of the site, extending and improving it, and nestling standalone pavilion buildings within this landscape. We used modern methods of construction to reduce loading over the tunnel and to speed up construction, reducing the need for on-site trades. The development is also car free except for mobility parking spaces.

Weplanted over 2400 new trees, engaged the local community, and incorporated nature trails for local schools to experience the diverselandscape in what is the UK’s densest local borough. It has become an exemplar of bringing sites like this back into beneficial use. A real success story.

On a personal level, can you tell us a little bit about your student days and the battle for Tolmers Village?

When I firstarrived at University to study architecture at the Bartlett School of Architecture at UCL, I ended up living in lodgings in the area around what was then called Tolmers Village - just north of Drummond Street in Euston. Back in those days, voracious developers were marching through large swathes of London, demolishing buildings to redevelop office buildings which were often then left deliberately empty to increase demand, and hence the revenue streams of developers.

A famous example of this was Centre Point which, when constructed, stood empty for almost 10 years. At that time a similar fate awaited the community around Euston as the Euston Road was being widened to accommodate ever increasing levels of traffic.

A group of radical architecture students from the Bartlett, together with a local community group, set about trying to prevent this destruction.We succeeded in ensuring the planned development was halted and replaced with a more appropriate redevelopment. Itis one of the first examples of community action impacting upon the outcome of a development proposal. This included the famous Drummond Street community, which remains but is now seriously threatened by the advent of High Speed Two (HS2).

We hear that you cycled across America from west to east coasts, then across Ireland and on to London via Wales – a trip of about 4,500 miles. Why?

Good question – why cycle 4,500 miles? Well, simply put, it was another challenge in life and having always tried to push myself to do things that seemed impossible (I’ve completed five marathons too) the opportunity to join a group of industry professionals on this once-in-a-lifetime adventure seemed too good to turn down.

The idea was the brainchild of Peter Murray, an avid cyclist and chairman of the NLA (New London Architecture) forum.As well as raising money for two very important charities – Article 25 and the Architects Benevolent Society – the trip investigated how American cities were adapting to promote cycling as a healthy and sustainable alternative to cars.

And the beekeeping and blues harmonica playing? How did they come about?

I have a beehive (19B) at my home – House 19 – as part of the sustainable agenda of the house. Bees are vital to our survival since they pollinate around 80% of the world’s plants and 90 different food crops. I have a ‘Flowhive’which is a new type of hive invented by a father and son duo in Australia and is much less invasive upon the bee colony when the honey is harvested – very clever.

Harmonica playing is just a hangover from my youth. I am an avid blues fan and love the sound a blues harmonica makesso I dabbled with playing and now just enjoy it - an easy instrument to carry around!

Lastly, Jestico + Whiles is a longstanding and valued member of the TenderStream business intelligence service. Have you found it to be a useful tool?

We have trialled many tender subscription services and TenderStream has by far the clearest, simplest and most legible interface of them all. It also provides access to tender opportunities worldwide. For a practice with an international outlook, such as ours, this is invaluable.

Interview: Gail Taylor

IMAGE CREDITS

1 - The House for the Future - Tony Hedland/David Williams

2 - The House for the Future - Tony Hedland/David Williams

3 - House 19 - Grant Smith

4 - House 19 - Grant Smith

5 - Greenwich Millennium Village (GMV) - Jack Hobhouse

6 - The Pavilions, Caledonian Road - Jack Hobhouse

7 - The Pavilions, Caledonian Road - Jack Hobhouse