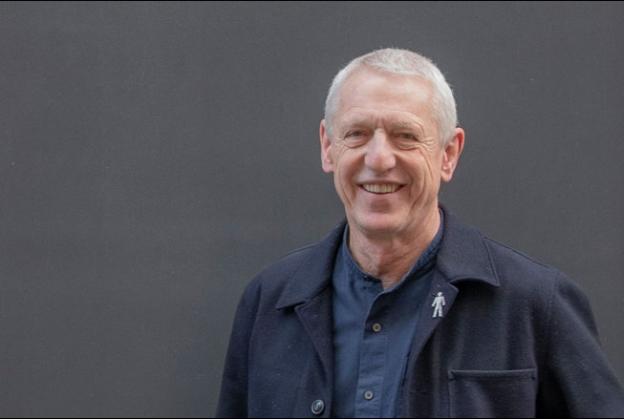

Amaury Greig, Partner/Director of Operations – Renzo Piano Building Workshop (Paris)

In 2012, Amaury Greig joined Renzo Piano Building Workshop’s Paris studio to work on the Paris Courthouse project. Next, he went on to work on the Ontario Court of Justice in Toronto and many other inspirational projects. He is now Director of Operations and Partner responsible for business development at RPBW. His background in geography has created a lifelong passion for place, physicality, and materials, which, as you will read, have translated into a career of putting humanity at the heart of RPBW’s work…

Hello Amaury,

When practice founder, partner, and Pritzker Prize Laureate Renzo Piano himself says, “One of the great beauties of architecture is that each time it is like life starting all over again,” what do you feel he means by this?

Every project is an adventure, and every project has its own unique context. I see this in two parts. The first is the human adventure, which includes discovering and responding to the ambitions of our clients and collaborating with large groups of specialists to bring a vision to life. Then there are the unique characteristics of the physical world - topography, geology, plant and animal life. Then there is the social context, and then the materials, structures, systems, the list goes on…

With all this, there is discovery in every project. When we start, we never know where we will end up, but a sequence of iterations can be traced that reflects our learning about the places, materials and cultures we discover along the way.

It’s always different; this is one of the best aspects of the profession, but it also takes a concerted effort to ensure we acknowledge and take advantage of experience while simultaneously looking at the world with fresh eyes. Renzo has always undertaken this exercise with wonderful agility, and it has become embedded in the Workshop’s culture.

RPBW prides itself on its ability to ‘sculpt light’. Can you elaborate on that a little, please?

Light is perhaps the most important material that the architect has to consider. First, research shows that exposure to natural light helps maintain the human body’s circadian rhythm, which keeps the body and mind in optimal condition. It also has an important impact on emotional and subjective well-being. In short, access to natural light helps people feel happier. Also, there’s a bit of magic in the dynamic nature of light throughout the day.

“(Light) has an important impact on emotional and subjective well-being. In short, access to natural light helps people feel happier”

There are many different building types, and many have pre-conceptions about their supposed required relationship to natural light. In many projects, a primary focus of our design efforts has been to bring light to places that typically avoided it - such as museums, courthouses, hospitals, and even operating theatres. In every case, we’ve been driven to develop an architecture that adapts, filters, modulates, or emphasises daylight to ensure the performance requirements of the space are delivered and makes the human experience better.

And how would you define the ‘Genius Loci’?

Genius Loci is Latin for ‘the spirit of a place.’ It’s what makes a site unique and special…the soul of the place. For us, it is important to consider that carefully in order to uncover the material and cultural values that we want to use to develop an architecture that is meaningful to the people who will use it.

Taking all these considerations into account, how do they manifest in landmark projects such as Canada’s Ontario Court of Justice in Toronto?

A courthouse is the physical expression of a justice system. As a civic place, it also expresses the ambitions of a society. In countries such as Canada, the fair and transparent administration of justice arguably plays an increasingly fundamental role in upholding democracy and keeping society together. The contemporary courthouse is no longer the dark and heavy building raised on a plinth high above the street, dissociated from society. It is a civic institution that brings together the diversity of cultures that compose Canadian society.

The Ontario Court of Justice strives to be a welcoming and open space, and the extensive use of glazing on the lower levels creates a visual relationship between the city and the interior of the courthouse – difficult to achieve for a high-security facility. The project was designed to be lower than the allowable height limit to provide a better fit with the skyline and to complement, rather than compete with, the iconic heritage-listed Toronto City Hall. This while complementing Osgoode Hall, a national historic site immediately to the south.

In many ways, the design approach strove to be generous and reflect a very Canadian interpretation of a multicultural, transparent, and accessible society. Dignity for the over two-thousand people a day that go through the doors was a driving factor in the architecture of the project.

“…the design approach strove to be generous and reflect a very Canadian interpretation of a multicultural, transparent, and accessible society”.

Moving on to the Grand Paris-Nord University Hospital, how have your designs made a clinical situation more humane than the often grim and frightening environment that so many hospitals present?

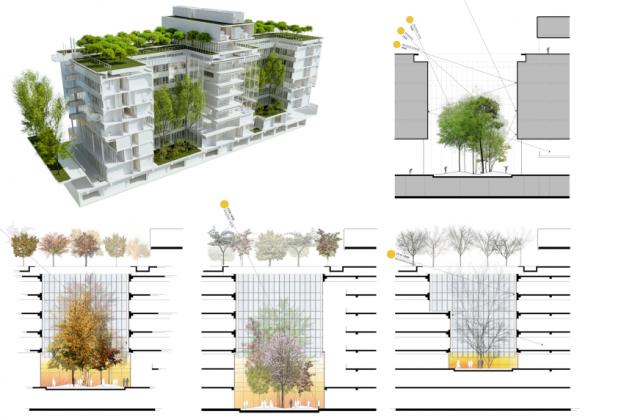

In all of our projects, we are driven by a desire to provide the most meaningful solution. The Hospital is located in a fairly dense low-rise urban fabric, and the challenge undertaken by my colleagues, Antoine Chaaya and Thorsten Sahlmann, was to consider how to fit a 1200-bed, 190,000 sqm space into this context.

The project is low, with trees enveloping the site, and strategic setbacks defined to create public squares. The extensive green roof serves both to reduce the urban heat island effect, and visually embed the building in the city of Saint-Ouen. These are the first acts of being a generous neighbour, improving the conditions of those already living in the area.

Convinced that access to fresh air and light is fundamental to human well-being, we have designed a hospital with an approach that assembles T-shaped modules which generate a sequence of large sunken patios planted with trees. This composition has the advantage of avoiding deep floor plates and allowing for natural light in all rooms and services, including workplaces.

Villa Sauber, now a museum, is one of Monaco's last Belle Époque villas. What has RPBW’s involvement in this project consisted of, and how do you feel the practice has contributed?

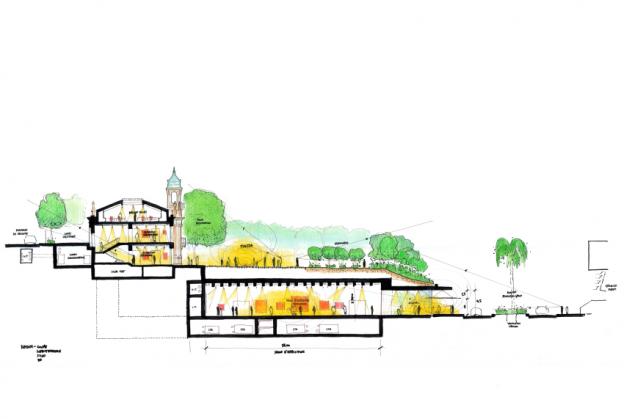

Villa Sauber is one of two locations that make up the National Museum of Monaco. We have been commissioned by the Principality to renovate and expand the museum. The existing 19th century villa is an exceptional site with a beautiful garden. Over time it has become an oasis as the city has densified around it. So, it is both a valuable natural space and a historical archive of the city’s past.

The villa is composed of rooms that, by their scale and organization, limit the types of works that could be exhibited, so expansion became necessary. When we started working on the project, it became clear that the need to expand the capacity and scale of the museum risked jeopardizing the existing qualities that made this place so interesting.

Led by Daniele Franceschin, the team has developed a project that carefully inserts a larger gallery space below the garden, creating a new entrance on the low side of the site and connecting into the villa from below. The garden above the gallery is embellished and becomes a sculpture park. At the same time, public throughways traverse the site to improve pedestrian circulation and generate a relationship between the formally walled villa and visitors.

Concealing the gallery below the landscape, renovating a historical building, and allowing people to flow through the landscaped site has created an almost subversive quality in the context of Monaco.

There can be no more sensitive subject than a child whose health is failing. RPBW states that all its work is informed by people. How has this been achieved with the design of the Children’s Hospice in Bologna, Italy, and where does the idea of levitation come in?

This is true; hospices are places of tremendous tragedy. As designers, there is only so much we can do, but we can and must work to provide comfort for those facing unbearable situations. The project was commissioned by the Maria Teresa Chiantore Seràgnoli Non-Profit Hospice Foundation to embody the approach it has always adopted to palliative care: to associate functionality and quality services with the nobility of beauty.

Given what we know about how nature can have a positive impact on well-being, here we were also inspired by the notion of “alleviating” – both lifting the spirit and easing pain – and the design seeks to provide relief and comfort; the essential qualities of a hospice. Living among the trees evokes childhood dreams of treehouses and creative freedom, reinforcing the idea of a nurturing and uplifting environment for the children and families that spend time here.

“Living among the trees evokes childhood dreams of treehouses and creative freedom, reinforcing the idea of a nurturing and uplifting environment for the children and families that spend time here”.

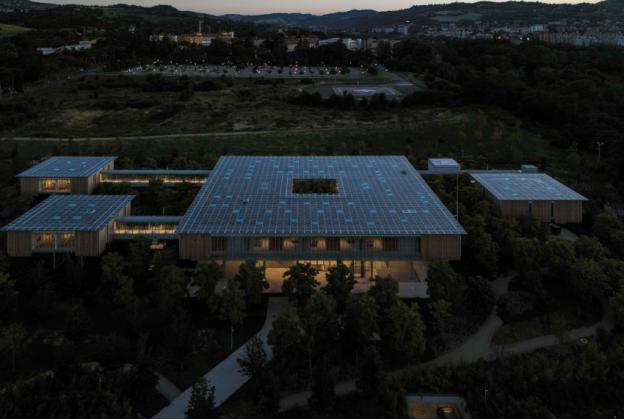

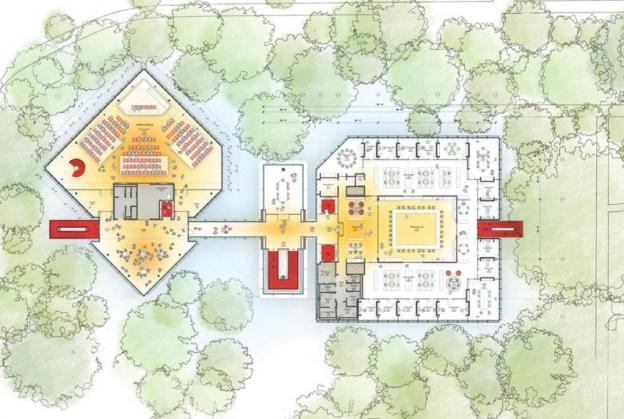

At the Johns Hopkins University campus in Baltimore, USA, the new SNF Agora Institute Building will strive to ‘be the home of the academic and public forum devoted to identifying, designing, and testing new mechanisms to strengthen civic engagement and inclusive dialogue worldwide.’ How is this reflected in RPBW’s designs?

I believe that what really brings us together as a group at RPBW is a shared commitment and passion for developing places for people. By this I mean places for human gathering, sharing, and communication. It reflects an optimistic vision of the world, but also how we work.

The project for Johns Hopkins, led by Luigi Priano, is driven by this idea of bringing people together, encouraging people to traverse the site between the two transparent volumes, and connecting with the ongoing activities inside. The scale of the buildings and a careful relationship to the topography create a public space that also happens to have enclosed transparent volumes where students, faculty, and the community at large can gather and pursue this experiment we call democracy. An experiment that, by the way, requires continued effort, support, and nurturing in places like the Agora.

On a more personal level, you studied geography at the University of Victoria and Political Science at the Institut d’Études Politiques de Paris (Sciences-Po) before studying architecture at the University of British Columbia in Canada. What inspired you to make the transition from geography to architecture? Are they intrinsically linked for you?

I started my studies only knowing that I had an interest in trying to understand what makes places different and how they come to be. I was interested in the natural world and became fascinated with human settlements - the social sciences and geography in particular were a good point of entry. Ultimately, I learned that I’ve always been animated by an optimistic desire to build in a more physical sense, and architecture provided this bridge between larger environmental and social considerations and the very physical act of assembling materials into structures.

If you hadn’t become an architect, is there any other career path you might have taken?

I’ve had lots of very different ideas along the way! I recall my father gave me a copy of Ian McHarg’s Design with Nature when I was young, and this had a lasting impact. For a long time, I pursued an interest in regional and urban planning.

What might we find you doing outside work?

I could be hiking in the forest with my family, fixing something, gardening, on the water in a boat, drawing, or reading...

And finally, RPBW is a valued member of Tenderstream. As the person responsible for business development at the practice, in what ways do you find the service valuable?

RPBW is fairly unique in that we are a relatively compact group of about 120, yet we currently have projects underway in 15 different countries. Tenderstream is another tool in the kit that helps us have a vision of project opportunities worldwide that is curated in coherence with the types of projects that are relevant to RPBW.

Interview by Gail Taylor, Features Editor

Image credits

Both offices in front of the CERN Science Gateway Building in Geneva

1-3

Ontario Court of Justice

Toronto, Canada

2016 – 2023

Client: Infrastructure Ontario for the Ministry of the Attorney General + EllisDon Infrastructure

Renzo Piano Building Workshop, architects

in collaboration with NORR Architects and Engineers Ltd. (Toronto)

Images Scott Norsworthy

Competition, 2016-2017

Design team: A.Belvedere (partner in charge), N.Aureau, A.Greig, A.Karcher, A.Landeiro, B.Plattner (partner) with D.Franceschin, S.George, J.Irace, A.Nizza, M.Pimmel and L.Antonio, G.De Juan; A.Bagatella, D.Tsagkaropoulos (CGI); O.Aubert, C.Colson, Y.Kyrkos (models)

Design Development, 2017-2023

Design team: A.Belvedere, A.Greig (partner and associate in charge), F.Hebel, A.Landeiro, W.Scheske with A.Chaaya (partner), T.Ohira, M.Pimmel, D.Rat, I.Soto, J.Vella and T.Borges; A.Bagatella, T.Garofalo, D.Tsagkaropoulos (CGI); O.Aubert, C.Colson, Y.Kyrkos (models)

Photo credits © Scott Norsworthy

4 - 6

Hôpital Universitaire Saint-Ouen Grand Paris Nord

Saint-Ouen, France

2019 – in progress

Client: Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris

Renzo Piano Building Workshop, architects

in collaboration with Brunet Saunier Architecture (Paris)

Design team: A.Chaaya, T.Sahlmann (partner and associate in charge)

Photo credits © RPBW

7 - 10

Musée national de Monaco – Villa Sauber

Monte Carlo, Monaco

2019 – in progress

Client: État de Monaco (Direction des Travaux Publics)

Renzo Piano Building Workshop, architects

in collaboration with Franck Bourgery Architecte (Monte-Carlo)

Design Team: D.Franceschin (partner in charge)

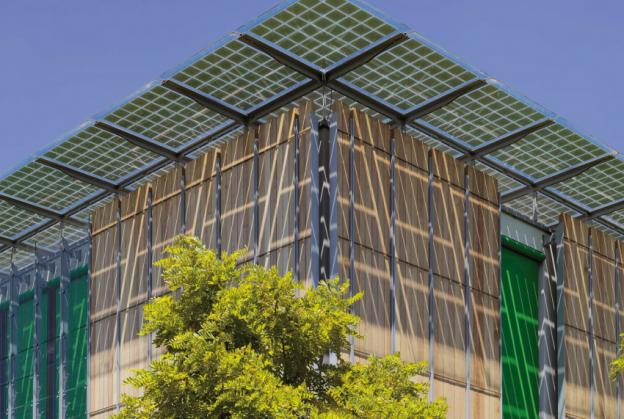

11 - 15

Children’s hospice

Bologna, Italy

2014 – 2023

Client: Fondazione Hospice Seragnoli

Renzo Piano Building Workshop, architects

Design team: G.Grandi, S.Russo (partner and associate in charge), A.Zanguio, E.Donadel, R.Parodi, S.Polotti, G.Semprini, O.Teke with V.Bonanni, M.Carroll (partner), A.Chiabrera, V.Costalonga, M.Ottonello, E.Trezzani (partner), Ch.Van der Hoven; G.Corsaro, B.Pignatti, A.Pizzolato, C.Zaccaria (CGI); F.Cappellini, D.Lange, F.Terranova (models)

Photo credits © Enrico Cano

16 - 18

SNF Agora Institute at John Hopkins University

Baltimore, Maryland, USA

2018 – in progress

Client: Johns Hopkins University

Design: Renzo Piano Building Workshop

in collaboration with Ayers Saint Gross, architects (Washington DC)

Design team: M.Carroll, L.Priano (partners in charge)

Photocredits © RPBW